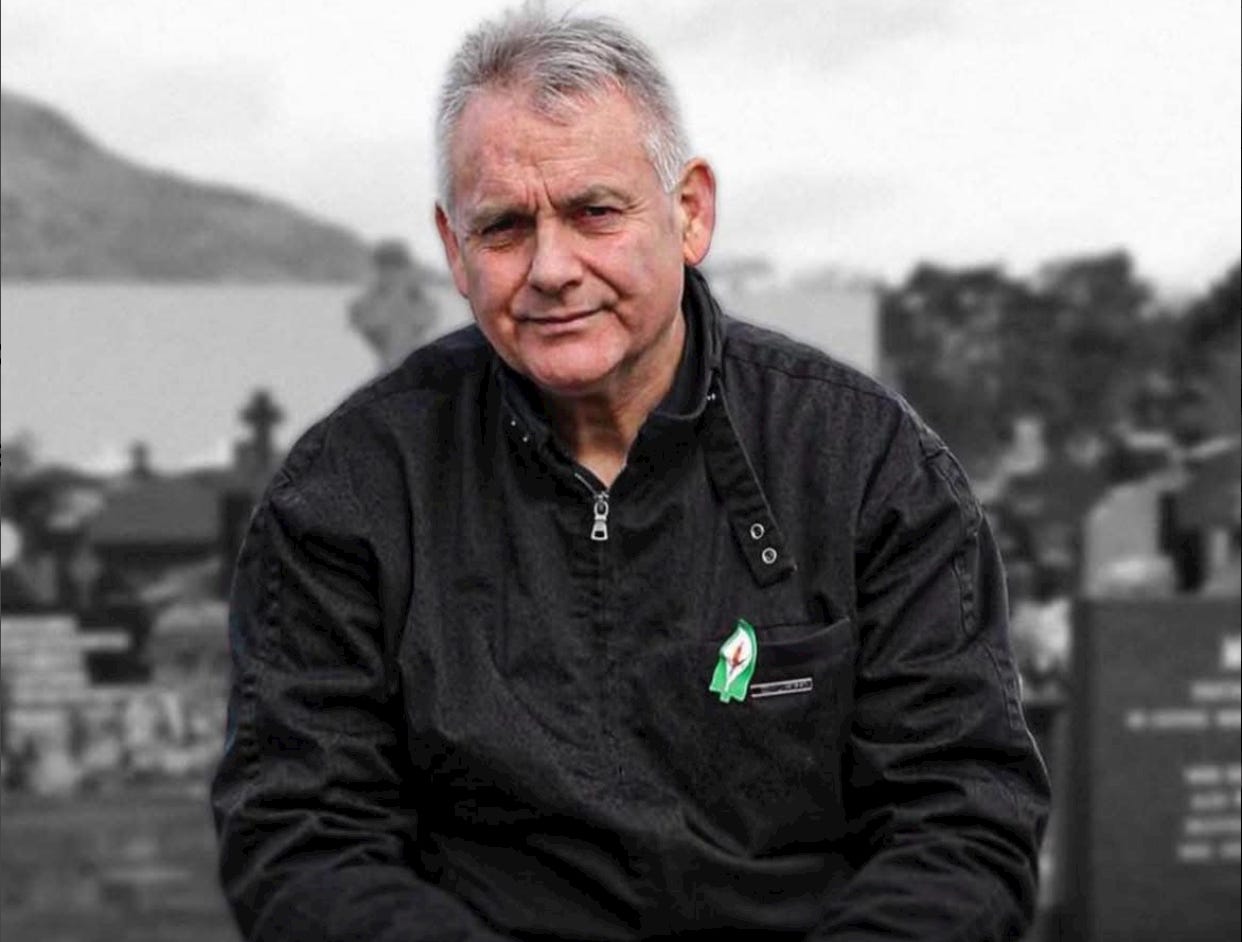

The Truth About Brendan "Bik" McFarlane

Brendan Bik McFarlane was a vicious sectarian murderer.

On a damp, unremarkable Wednesday evening, August 13, 1975, the Bayardo Bar was doing what Belfast pubs did best: serving as a refuge from the chaos of the sectarian civil strife we like to euphemistically call in Ireland “The Troubles” like it was an irritable bowel movement rather than a vicious sectarian civil war. The pub was packed with the usual assortment of humanity—old men nursing pints, young couples stealing glances, and everyone in between, all united by the simple desire to forget, for a moment, the grinding misery of the Troubles. But history, that cruel and capricious playwright, had other plans. Just before the last call, a stolen green Audi rolled up outside, carrying three men from the IRA’s Belfast Brigade. Among them was Brendan “Bik” McFarlane, a 24-year-old Ardoyne man who was about to orchestrate a night that would sear itself into the collective memory of a city already scarred by many such nights.

Seamus Clarke and Peter “Skeet” Hamilton, the other two members of this grim trio, stepped out of the car and made their way to the pub’s side entrance on Aberdeen Street. What happened next was a grotesque ballet of violence. One of them raised an Armalite and opened fire, cutting down 63-year-old doorman William Gracey and his brother-in-law, 55-year-old Samuel Gunning, as they stood chatting outside. The bullets didn’t discriminate; they never do. Inside, the pub was alive with the sound of laughter, clinking glasses, and off-key singing. The gunmen's accomplice then walked into the crowded bar and threw a bag with a ten-pound bomb inside it.

The bomb exploded with an all too familiar Belfast roar that shattered more than just bricks and plaster. It shattered lives. Panic erupted as patrons scrambled for safety, many fleeing to the toilets as if a flimsy bathroom door could shield them from the wrath of men who had long since abandoned any semblance of humanity. When the dust settled, the bar was a tomb. Joanne McDowell, 29, a civilian with no stake in the war raging outside, lay dead beneath the rubble. So did Hugh Harris, 21, a member of the UVF, whose allegiances mattered little in the end. Seventeen-year-old Linda Boyle was pulled from the wreckage alive, but her youth and innocence couldn’t save her. She died in the hospital eight days later, a child’s dreams extinguished by a conflict she didn’t start and couldn’t stop. Over 50 others were injured that night, their bodies and spirits broken by an act of violence as senseless as it was savage.

As the trio made their escape from the carnage they had just unleashed, they indiscriminately fired their Armalite guns at a group of women and children who were queuing at a taxi rank. McFarlane was a former student priest with evil in his heart instead of god. McFarlane and his accomplices were quickly apprehended and were jailed for life.

David Beresford, the author of the 1987 book Ten Men Dead, about the hunger strikes, said Bik wasn’t chosen to be a hunger striker because McFarlane was perceived to be a “sectarian mass-murderer”.

“Biks” story doesn’t end here.

In November 1983, just two months after the audacious Maze Prison escape, the IRA struck again, this time kidnapping businessman Don Tidey. The supermarket executive was held captive in a remote hideout in Derrada Wood, near Ballinamore, for over three weeks. His ordeal ended on December 16th, when a search party of gardaí and army personnel finally discovered the hideout. But the rescue came at a terrible cost.

As the search party closed in, an IRA gang opened fire. Pte Patrick Kelly and Recruit Garda Gary Sheehan were gunned down in the chaos. Det Sgt Donie Kelleher was also shot and seriously wounded before the gang fled into the wilderness.

Ronan McGreevy and Tommy Conlon write in their book “The Kidnapping”.

Many years later Garda Sergeant Joe O’Connor, a trainee on the day, would recall the fateful moment in court. “I heard a groan or grunt where Garda Sheehan had been,” he said, recalling that the young recruit’s feet went from under him as blood poured from multiple wounds; his cranium was shattered by a bullet and his brain exposed.

The 23-year-old, who had begun garda training only three months earlier, died instantly. His garda cap, fastened by its chinstrap, remained on his head. Patrick Kelly, thirty-five and a father of four, was shot with a line of bullets from ankle to head and fell backwards. Kelly did not die instantly; he slowly bled to death. His comrades heard him plead: “Please don’t leave me, I’m not going to make it.”

The once quiet woods were now stained with the blood of the Gardai and an Irish Soldier.

Among the suspects was Brendan McFarlane, one of the Maze escapees who had been seen in Leitrim around the time of the kidnapping. Gardaí quickly named him as a key figure in the Tidey abduction, even before forensic evidence confirmed his fingerprints were all over the hideout. A garda at the scene later identified McFarlane as one of the gunmen who had fired directly at him during the escape. The evidence was mounting, but McFarlane remained elusive.

In 1986, McFarlane’s luck ran out. He was arrested in Amsterdam and extradited back to Northern Ireland, where he was slapped with an additional five-year sentence for his role in the Maze escape. But justice for Derrada Woods remained elusive to the authorities. Gardaí chose not to pursue charges against “Bik” while he was locked up in the North. It wasn’t until January 1998, when McFarlane was arrested on a bus in Co Louth, that the case was reignited. He was charged with falsely imprisoning Don Tidey, possession of a firearm with intent to endanger life, and possession of a firearm for an unlawful purpose.

What followed was a legal marathon that dragged on for a decade, weaving its way through the High Court and eventually to the Supreme Court. McFarlane, ever the nefarious enigma, refused to disclose his whereabouts from September 1983 until his arrest in Amsterdam in 1986. His trial finally began in June 2008, and the State’s case hinged on a chilling alleged confession: “I was there, you can prove that, but I will not talk about it,” McFarlane had reportedly said in custody. He later added, “I am prepared for the big one.”

But the confession, taken at Dundalk Garda station a decade earlier, was deemed inadmissible by the Special Criminal Court. The rules of evidence had changed, and the State’s case began to unravel. To make matters worse, gardaí had lost three key items from the hideout—a milk carton, a plastic container, and a cooking pot—all bearing McFarlane’s fingerprints. The prosecution managed to salvage the fingerprint evidence by arguing that photographs of the prints were still admissible, but it was a hollow victory.

In the end, the State threw in the towel. McFarlane walked free, leaving behind unanswered questions and unhealed wounds. The Don Tidey kidnapping and murders of Garda Gary Sheehan and Private Patrick Kelly were a grim reminder that the Troubles didn’t just affect those in the “North”, which still lingers today.

Which brings me to the eulogising of Brendan “Bik” McFarlane by Sinn Féin’s high priests of historical amnesia—what a masterclass in mental gymnastics! Here we have a man, a convicted sectarian murderer, whose hands are stained with the blood of the innocent, whose fingerprints linger like ghostly accusations at the scene of a kidnapping, whose legacy is a trail of shattered lives and broken families. And yet, Sinn Féin’s luminaries, their faces solemn, their words dripping with reverence, as though they’re canonising a saint rather than sanitising a sinner.

Can you picture Micheál Martin or Simon Harris standing up to sing the praises of a man like MacFarlane? The public would rightly howl them out of office, and the media would feast on their carcasses for weeks. But when Sinn Féin does it? Crickets. Or worse, a sympathetic nod, as though this is all just part of some grand, misunderstood narrative of “struggle.”

Let’s not mince words here. McFarlane and his accomplices didn’t just kill—they massacred. They sprayed bullets into a crowd of women and children. This isn’t some romanticised “freedom fighter” nonsense; this is cold-blooded, sectarian butchery. And yet, Sinn Féin’s leaders, with their carefully curated air of moral superiority, have the gall to eulogise him as though he were a hero. It’s enough to make you wonder if they’ve ever cracked open a history book—or if they’ve just decided that history is whatever they say it is.

The families of those murdered by McFarlane and his ilk—where’s their justice? Where’s their closure? Sinn Féin’s leaders may have mastered the art of political theatre, but their performance here isn’t just tasteless—it’s a slap in the face to every decent person who believes that murder is murder, no matter what flag you wave or what cause you claim to serve.

So, let’s call what Sinn Féin is doing for what it is: not a eulogy, but an insult.

Still a great read the second time around